Miles Grody, Potomac, MD

“When is the last time you saw someone walking down the street carrying a staff?” That is the question I asked a couple of my students a few months back as I was just introducing them to the weapon. They responded that they could not remember seeing anyone. That led me to the next question: “So why should we bother training with something that we’ll likely never use because it won’t be with us?” As usual when I have asked these questions to new students, the elicited reaction was that of puzzled looks.

I do not ask these types of questions to be aggravating; I ask them because I believe individuals can often train more effectively if they have an understanding—or at least an inkling—of the types of benefits they might receive from the efforts they are expected to exert. The objective of this article is to explore responses to these questions that will help us achieve a more specific appreciation of what we might gain from staff training in today’s day and age.

One easy answer to the above questions is that staff training is part of our gongfu and North American Tang Shou Tao tradition. We train in many techniques and sequences that have been passed down for decades, if not centuries. This answer can even call to mind the origins of gongfu, including the early monks of the Shaolin Temple who modified Buddhist breathing and meditation exercises into self-defense maneuvers and strategies based on the natural movements of animals. Personally, I like this connection between my staff training today and the origins of gongfu, reflecting upon how these early Shaolin monks further enhanced animal inspired self-defense techniques to incorporate what were then actually practical weapons. Meditating on tradition and romanticizing the origins of gongfu, however, do not present a satisfactory answer to why we still train with staffs today. If there is no present day benefit regarding self-defense or fighting with a staff, then it would seem that staff training might be better as one of those skill sets we drop in order to devote our energies to more productive and relevant areas of our art.

Fortunately, tradition is not the only answer. After discussing the introduction of staff training in gongfu’s history with students who are new to weapons, I often shift the topic and ask when in their study of our association’s various martial arts curriculums have they covered weightlifting. Of course, anyone who has trained with us for a while should realize that weightlifting, at least in the western sense, is not part of any of our oriental martial arts curriculums. What newer students may not realize is that weapons training serves as one of our alternatives to western weightlifting exercises.

In western exercise regimens, people generally lift weights to build muscle mass and sculpt their bodies. Our Chinese internal arts approach is markedly different. While we do not lift weights, we do train with heavy objects—our weapons. As many of us have experienced, to our pain and exhaustion, Vince Black often introduces us to new weapons by requiring us to work with the heaviest available. The objective of this approach is not to ease us into the weapon, but to accelerate the programming of our bodies by “burning in” the movements so that they can be firmly internalized. The goal is not to build big muscles, but to develop the connections and balance between our muscles, tendons, ligaments and overall skeletal structure that promote the enhancement and execution of our internally oriented techniques. This is not to say that our association’s type of training does not result in a sleek or svelte body image. In fact it may, depending on your preferences. But instead of a bulky, tension holding physical frame, it leads to a wiry, looser, better connected, power projecting frame, which is far different from the impacts that western weight training methods have on the body.

So the response that weapons serve as our alternative to weight training may help answer why we train with weapons, but it does not answer why we train with a staff. Traditionally, in Shaolin-based martial arts systems, the staff is the first weapon introduced to students, and the same is the case in our Shen Long system. This has to do with the nature of the staff itself. It is relatively simple, being long, straight, symmetrical, and balanced. What you experience along one end of the staff is exactly the same as what you experience along the other end. In our xingyiquan training, as well as in other Chinese martial arts, we strive to develop a symmetrical, integrated approach to channeling energy through our bodies. The staff, which embodies these qualities, therefore provides an ideal construct for our introduction to weapons training. From a combat perspective, fundamental features of the staff include the facts that it requires both hands to wield and control, and what can be done with one end of the staff can also be done with the other end. As opposed to other “early stage” oriental martial arts weapons, such as a saber, knife, stick or sword, each of which can be wielded in a single hand, the staff requires both hands to be manipulating it simultaneously for offensive and defensive maneuvers to be performed. The requirement of involving both hands promotes equal development of the right and left sides of the body, which is essential not only to staff training but also to the empty-hand training that constitutes a central focus for many of us in our internal martial arts pursuits.

In our Shen Long curriculum, students are introduced to staff training through the form Shaolin Bang. The form moves along the directions of a compass (north, east, south and west), and can become tedious to those who are unclear about the qualities they are trying to develop as they are introduced to the form. Many of the strikes demonstrate the power that can be generated through an oppositional movement of the arms. For instance, after opening by moving to a right bow stance, the form begins with a left low strike followed by a left high strike, both delivered from a stationary position. The power for these low and high strikes is produced by snapping the right hand in toward the right hip while simultaneously shooting the left hand across the body, with equivalent degrees of force projecting through both hands. Later in the form a similar energy is generated when delivering a downward overhead strike, involving a right bow stance with the right hand projecting downward and forward, the left hand simultaneously pulling upward and stopping on the left hip, and the staff completing its motion parallel to the ground. Such oppositional movements as this overhead strike can be compared to the empty-hand leveraging movements of our arms and upper torso with the arm bar we practice in the second step of Ba Tang Quan, and help to cultivate the energy used when executing our metal splitting fist element, piquan.

Although at first Shaolin Bang might impress students as repetitive and boring, a more careful review reveals that the movements become progressively more involved. After beginning with mostly stationary strikes and teaching how to reposition our hands from one end of the staff to the other, later points of the form require execution of these same movements with a step or a turn. Because the staff adds weight to our upper bodies, effectively executing a stable strike or a block while completing a forward or backward step enhances our grounding and rooting, key fundamentals for every internal martial artist. The form ends by introducing a short series of staff spins—staff spinning becomes more elaborate in our more advanced Shen Long staff forms, and is a skill I have generally regarded as an integral part of learning staff basics.

In order to learn advanced movements, it is essential to first learn the basics that underlie the more advanced movements. I regard Shaolin Bang as something of a catalogue for basic staff movements in the Shen Long system. As my students become competent executing the form on one side (i.e., beginning by stepping their left foot back into a right bow stance), I then direct them to learn the form on the other side (i.e., beginning by stepping their right foot back). After all, we should be equally competent executing our basics on one side as well as the other. Practicing the form on both sides not only helps balance how we develop our bodies and energy through staff training, but also helps enhance our comfort with making the staff an extension of ourselves. Making the staff an extension of ourselves involves the concept of moving harmoniously with staff, and being aware not only of the parts of the staff we are actually touching with our hands, but of the entire length of the staff, from one tip to the other.

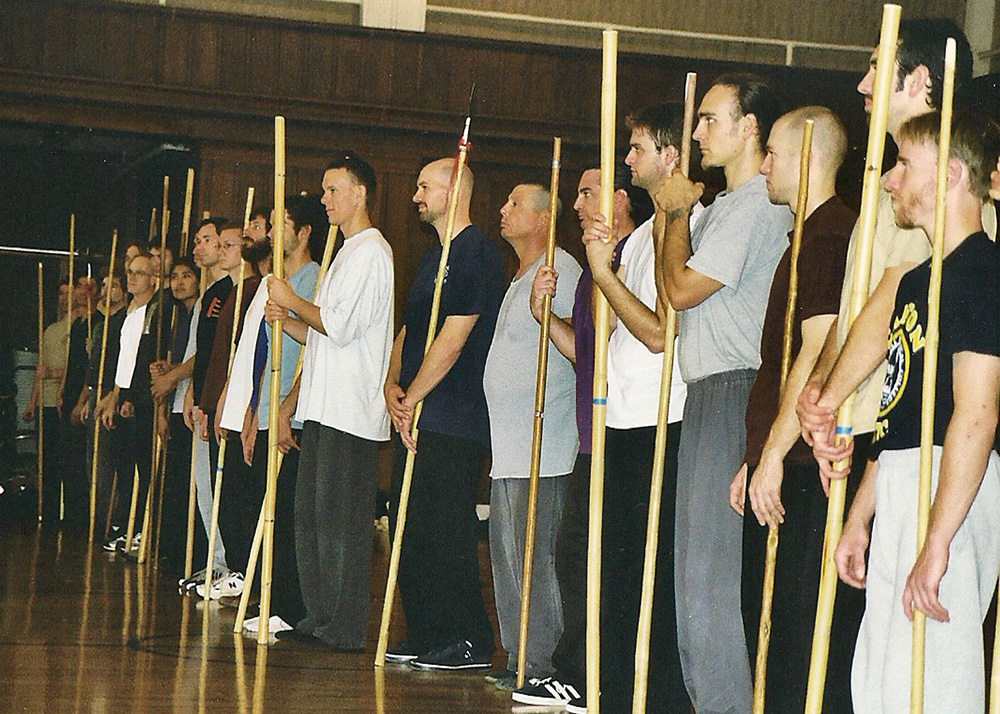

It is difficult to know if we are being effective at making the staff an extension of ourselves unless we have some way to test this. Shaolin Bang solves this through our practice of the two-person version. Executing the two-person version of Shaolin Bang requires that you become aware not only of the timing of your movements in relation to those of another person, but also of where on your staff you are contacting your opponent’s staff. As this awareness becomes more natural, the sense of the staff being an extension of your body becomes more developed. You can also hit a training partner’s staff harder with your own staff than you might hit your own arm against a partner’s arm (for example, think of our seven star drills), because there are no pain sensors in our staffs. Consequently, practicing two-person staff maneuvers can be an effective way to gain a better appreciation of how to project power through your strikes.

When practicing two-person drills, it is important to be aware of and properly match the characteristics of your own weapon with those of your partner. A few months back, my students purchased non-tapered six-foot wax wood staffs so that we could all train in two-person staff techniques with comparable weapons. I recommend practicing two-person staff routines with staffs of identical dense wood and weight to prevent a weaker staff from being prematurely dented and broken by a stronger staff. Our non-tapered wax wood staffs have proven effective in this regard.

For those of you who may be new to the staff, I hope this article gives you an opportunity to offer constructive responses when your instructor asks you why we train with staffs. To summarize, some answers might include:

- Staff training is part of our gongfu tradition.

- Staff training represents our alternative to western weightlifting.

- Staff training enhances physical qualities and dynamics that we develop and rely upon with our empty-hand techniques.

- Staff training enhances right/left symmetry in the ways we move.

- Staff training improves our rooting and grounding.

- Staff training introduces us to how a weapon can become an extension of our body.

- Staff training can enhance our understanding of how to project power through our techniques.

I wish you well with your practicing, and look forward to hearing your thoughts about staff training the next time we see each other.